I slept with the Light and

Became Pregnant with Love

I slept with the Light and

Became Pregnant with Love

Mysticism, spiritualism, minimalism, conceptualism, historicism, philosophical aphorisms, and a certain amount of self-referentialism, are all threaded throughout Angela Larian’s art. In combination, these help to activate and energize the familiar, creating something fresh that pulls us between the realm of the seen and the unseen. But for me, all these “isms” take second place to the strong sense of design and visually compelling presence in her work. Her use of Persian texts, at times transformed into disentangled words, and her sleek geometrical grids, which often merge with writing, are what attracts me to her art; neither perhaps surprising given my own academic interests and Angela’s Iranian cultural heritage.

Khoda, the Persian word for God, and its related phonemes figure prominently in the current exhibition. While its use dates back to ancient Iran, as written in Modern Persian it comprises the consonants kha’ (distinguished by a point above the letter) and dal, and the long vowel alif, a single vertical shaft. In this word, the letters kha’ and dal are traditionally written connected followed by the unattached alif. In Angela’s renditions of Khoda, all letters may be connected in a rectilinear manner, something which has a long history in Iran, especially in architectural decoration; at other times the letters are detached from one another, a more contemporary phenomenon in Persian calligraphy, while still retaining the coherence of the word.

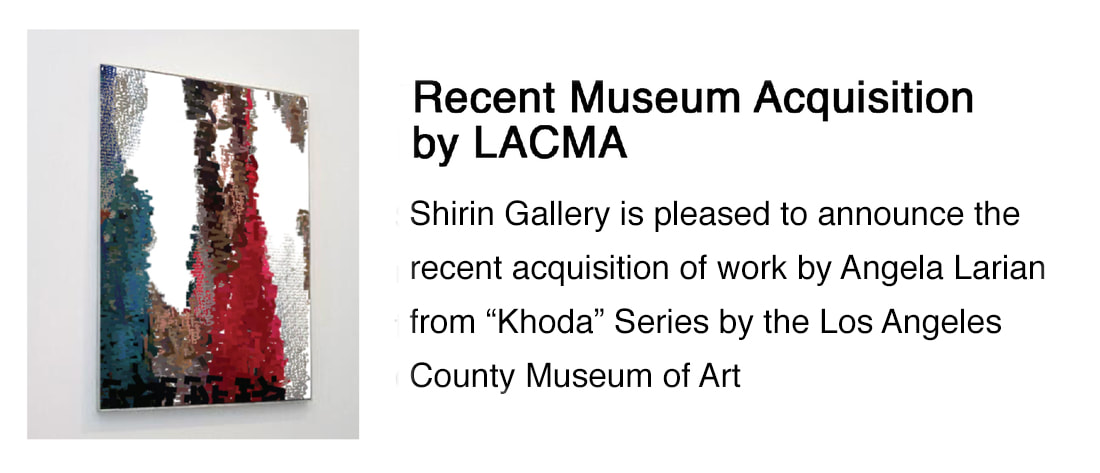

Rendered as the uncoupled or disengaging kha’-dal-alif, and repeated hypnotically, in video as well as in still imagery, Angela’s Khoda has a different vitality, a new presence. In the large-scale versions of Khoda printed on metal, the words cluster and unravel; the colorful letters become abstract forms, modular units of architectonic design. The negative void between the letters achieves its own visual primacy. And yet, for those who read Persian, the kha’-dal-alif are endlessly reconstituted and comprehended as the word Khoda, in much the same way as the deconstructed letters G-O-D will always be identified as God (or dog). In the interactive video version of Khoda, the word takes on another function, actuated by the person engaging with the work who is thereby empowered.

Related in meaning and form, the word Khoda’i is the active counterpart to Khoda, and perhaps can be understood as “godly,” or else “masterly” as in Angela’s interpretation. She runs together the letters of Khoda’i, which is inscribed over and over again within the geometric grid covering the back and seat of a silvery metal chair. On a coppery metal bench, Khoda’i is rendered in groups of four, in which the final letters ya’ intersect with the alifs to create a dynamic design. It is left for the viewer to decide for whom these shiny, unyielding seats are intended.

There is a more clearly defined relationship between word and formal intent in two pieces which each incorporate the word Khod or self, which many believe forms the compound of the word Khoda (therefore signifying both God and self-created). Here, however, the interpretations are as complex and varied as each person who engages with the works. Entitled “Infinite,” one work has the openwork letters of Khod run together and repeated to form a grid; lit by LED lights and mounted within a mirrored box, the word reverberates still further. At the center of this design is an unobstructed square of mirror allowing the viewer to become part of the composition. The second piece, Labyrinth, is both more and less ambiguous; the word Khod is now rendered in the positive and in the negative space of an openwork blue-painted grid within a box, but in this instance the shadows thus formed echo the word. In a rectangular, undecorated space near the center is a compartment filled with a golden face mask depicting the ultimate self—the artist.

Some may recognize here in the use of Khoda/Khoda’i/Khod a subtle reference to the ideas of Friedrich Nietzsche, which is the artist’s intention. But Angela’s messaging is not always so arcane.

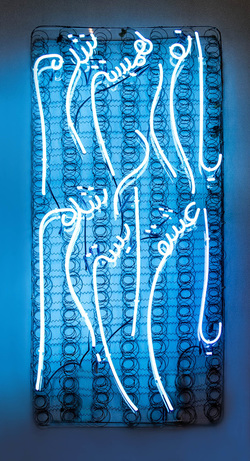

In one of her most engaging works, she combines a neon sign with the spring coils from a discarded mattress box spring. These are the types of materials well known since the advent of conceptual art. But here there are multiple layers of meaning that are far removed from any notions of conceptualism. The stylized Persian calligraphy of the blue neon text, in which the ascending and especially descending shafts of the letters are lengthened to become gay streamers, quotes from a poem that Angela once read, heard or dreamed:

با نور همبستر شدم با عشق ابستن شدم

I slept with the light and became pregnant with love

Quotations from Persian poetry having a subtle or overt connection to the object on which they appear are a common device in Iranian art from the twelfth century onward. For example, drinking vessels were inscribed with poetry about wine, candlestick holders with verses on the theme of the moth and the flame, and so on. Classical Persian poetry simultaneously brings to mind a number of images through the juxtaposition of the often ambiguous or metaphorical meanings of the words. Poems of this sort, which allude to the function of an object, when inscribed on the actual object, were intended to evoke one further image. The selection of such verses can to some extent be viewed as a kind of pun meant to be appreciated by those who used or else viewed the object.

Angela’s pairing of the verse and the mattress box spring follows in the tradition of earlier Iranian art. It is a practice that reveals a sophisticated way of thinking that not only gives primacy to the word, but which can render the intangible by visualizing something so entirely abstract, spiritual, mystical, and personal, as the notion of (divine) light.

Linda Komaroff

Curator and Department Head, Art of the Middle East

Los Angeles County Museum of Art