CONTEXT ART MIAMI

|

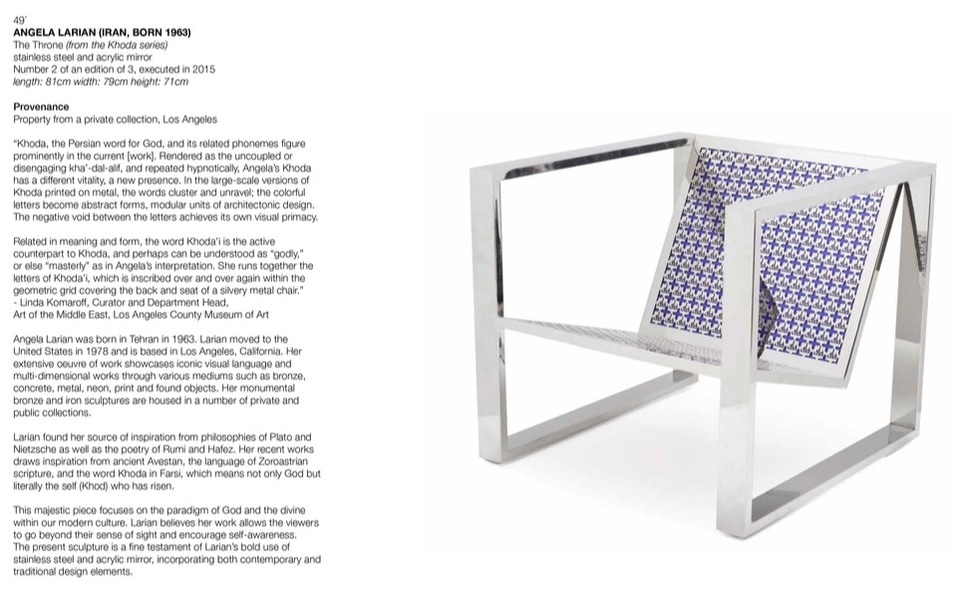

In the artist statement on her website, Los Angeles-based Angela Larian cites a variety of influences, including Plato’s and Nietzsche’s philosophies, as well as the writings of Persian poets Rumi (13th century) and Hafez (14th century). The blend, says the Tehran-born artist who moved to the United States as a 15-year-old in 1978, is “quite seamless.”

She cites one of Plato’s quotes which states that poets need holy inspiration — the sort that defies reason — to compose their verse, and his famous cave allegory prioritizes the invisible over the visible world. (Nietzsche, she adds, even composed a poem “To Hafez.”) The two medieval Persian poets, similarly, felt that the intangible world was more real than the one that is perceptible with the five senses.

“They both reiterated in their poetry how to let go of logic and the tangibles and dive into the world of mystery,” she says. “They always emphasized the ‘god within,’ rather than a monotheistic view of god outside of us that we need to fear.”

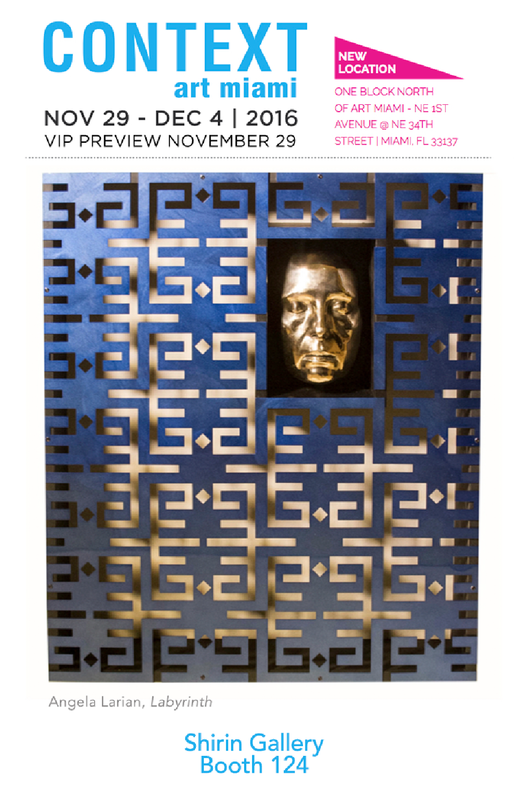

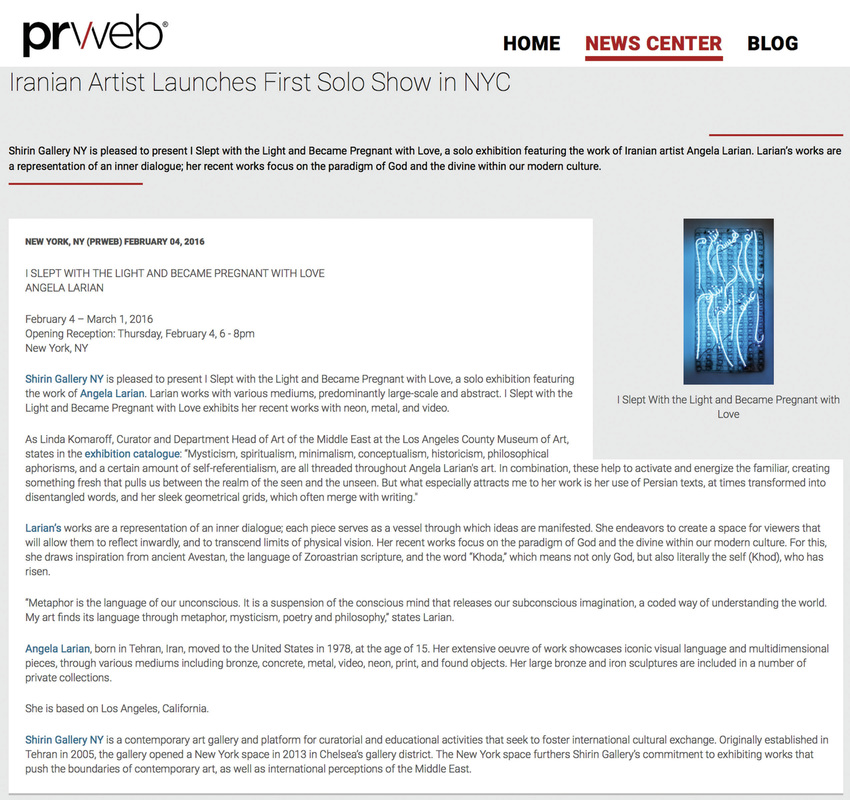

Larian, whose work is on exhibit in the solo show “I Slept with the Light and Became Pregnant with Love” at New York’s Shirin Gallery,” left Iran just before the Islamic revolution. Born Jewish, she says that she identifies as a religious artist in her “universal consciousness of humanity.”

The N.Y. show has its origins in an East Los Angeles junkyard, where Larian found objects for her sculptural pieces. The title of the show derives from a verse in Rumi, which Larian imagined being written on the surface of an old box spring mattress that she saw slated for recycling. (In so doing, she perhaps takes after another Jewish artist, Louise Nevelson,who also mined trash for her art.)

Asked the degree to which she self-identifies as an Iranian-born artist, and a woman-artist, Larian says she prefers not to emphasize identities, which she thinks tend to separate with boundaries.

“I desire for my work to transcend geography, politics, religion, and gender,” she says, while acknowledging “that may be a very challenging road to traverse.”

For an artist who is so well-versed in both Western and Persian philosophy, it’s no surprise that Larian asks herself big questions in both her life journey, and in her art: “What make me human? What makes me different from a machine?” she asks.

“I felt an inner-famine, a search for greater meaning in my life,” she says. “That is the inspiration behind my art.

She cites one of Plato’s quotes which states that poets need holy inspiration — the sort that defies reason — to compose their verse, and his famous cave allegory prioritizes the invisible over the visible world. (Nietzsche, she adds, even composed a poem “To Hafez.”) The two medieval Persian poets, similarly, felt that the intangible world was more real than the one that is perceptible with the five senses.

“They both reiterated in their poetry how to let go of logic and the tangibles and dive into the world of mystery,” she says. “They always emphasized the ‘god within,’ rather than a monotheistic view of god outside of us that we need to fear.”

Larian, whose work is on exhibit in the solo show “I Slept with the Light and Became Pregnant with Love” at New York’s Shirin Gallery,” left Iran just before the Islamic revolution. Born Jewish, she says that she identifies as a religious artist in her “universal consciousness of humanity.”

The N.Y. show has its origins in an East Los Angeles junkyard, where Larian found objects for her sculptural pieces. The title of the show derives from a verse in Rumi, which Larian imagined being written on the surface of an old box spring mattress that she saw slated for recycling. (In so doing, she perhaps takes after another Jewish artist, Louise Nevelson,who also mined trash for her art.)

Asked the degree to which she self-identifies as an Iranian-born artist, and a woman-artist, Larian says she prefers not to emphasize identities, which she thinks tend to separate with boundaries.

“I desire for my work to transcend geography, politics, religion, and gender,” she says, while acknowledging “that may be a very challenging road to traverse.”

For an artist who is so well-versed in both Western and Persian philosophy, it’s no surprise that Larian asks herself big questions in both her life journey, and in her art: “What make me human? What makes me different from a machine?” she asks.

“I felt an inner-famine, a search for greater meaning in my life,” she says. “That is the inspiration behind my art.